A black lace mantelet is probably one of the most pointless accessories in the history of western fashion. Flimsy and fragile, it is completely useless for what it’s pretending to be – a sheltering cloak. Purely from the standpoint of aesthetics, though, the sheer (hah!) futility of a lace mantelet is precisely what makes it so delightful. Frivolous, flirtatious translucence? With ruffles and ribbons on? What could be more charming?

These pretty black lace mantelets were highly fashionable through the middle decades of the 18th century. During the 1740s, ’50s and ’60s they were regarded as the height of chic. By the end of the 1770s they seem to have been considered somewhat passé, but for those middle decades, they were IT.

(clockwise from Top Left: Lady Lepel Hervey by Johann Zoffany c.1765 via National Trust Ickworth, Rosamund Sargant by Allan Ramsey c. 1746 via the Holborne Museum, Marie Congnard-Bathailhy, Jean-Etienne Liotard, 1757 via the Rijksmuseum, Jean Baptiste Massé (French, 1687–1767), ‘The Blue Muff’ c 1740 via Mary Hill Museum of Art.)

Not-at-all-coincidentally, one of my favorite pieces of 18th century portraiture is this exquisitely sensitive 1756 pastel of Madame Jean Tronchin by Jean-Etienne Liotard.

I had wanted a black lace mantelet for quite some time but the sort of lace net I wanted was pricer than I was willing to pay. I knew I would have to wait until the right fabric found me, and in mid 2023, just before we left Chile, I stumbled onto an ebay seller who was auctioning off the fabric collection of her late father. He had worked as a couturier in New York during the 1960s, and among her amazing listings were two gorgeous panels of black net lace.

One of the panels was irredeemably stinky. I put it through several washes and soaked it in everything from vodka to vinegar to Orvus Quilters Soap to a solution of bicarbonate of soda, but if anything, the heavy, fishy reek only grew stronger and I gave up and tossed it in the bin.

The second panel was perfect. I was ready to sew a mantelet!

The Marie Mantelet Pattern by Scroop Patterns felt just about right for this particular project. I like the Scroop mantle patterns a lot – they’re well drafted, with comprehensive and detailed instructions sets. If you’re new to historical sewing, or need a memory refresh, their instructions for period sewing and construction techniques are beautifully coherent and graphically solid.

To work with my delicate net, I spread the transparent fabric over the pattern and thread-traced the shapes. Then I thread-traced the pleating lines in bright contrasting thread, and then I carefully cut my pieces out.

Sewing was straightforward. Pins won’t hold in the loose net, but the net doesn’t fray, so I hemmed each piece by folding the hems once and basting with a bright and contrasting basting stitch , and then following the basting stitch with a simple running stitch done in fine black silk thread.

Assembly was done according to the pattern instructions. I sewed the center back seam of the hood and cartridge-pleated the gathers.

I basted the pleats into the cloak body and the hood.

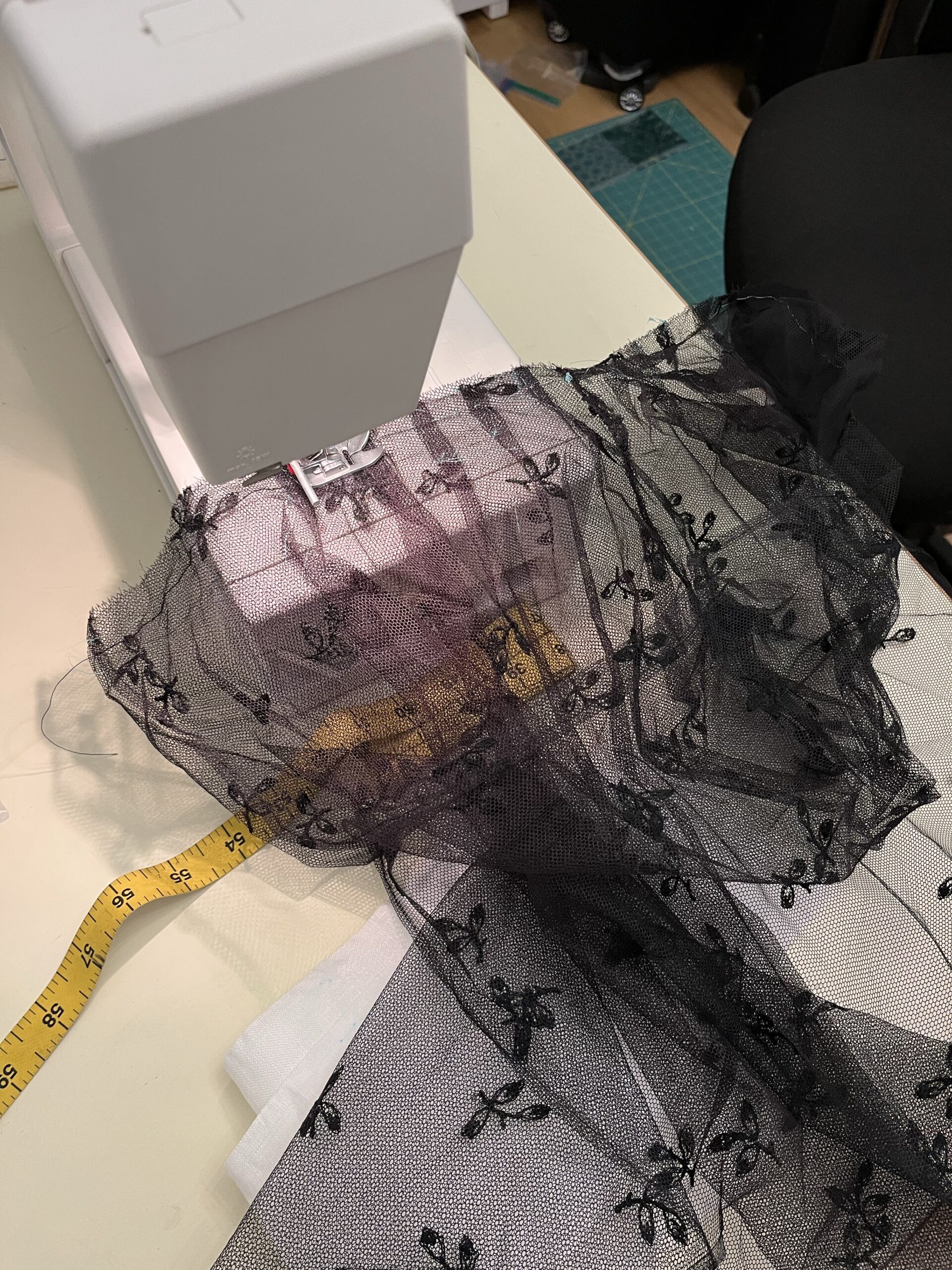

Then I basted and stitched the hood and body pieces together. I did use a sewing machine for this. The flimsy bits of fabric had more stability under the sewing machine’s presser foot than in my hands for hand-sewing.

I folded and basted down the raw edges of the neckband and then stitched it to the mantelet with whip stitches.

Mantelet made, I started on my coquettish little ruffle. I had originally intended a ruffle made from the same black net as the mantelet body. My piece of net wasn’t huge, but I calculated that if I heavily pieced my scraps, I would have just enough. That plan lasted exactly up to the point where my Mother-in-Law saw me bent over my weightless scraps of net, trying to wrestle them into something vaguely like even widths. Looking at me like I didn’t have enough sense to come in from the rain, she told me that life was quite short enough as it was, and for making a ruffle from lots of little scraps of this fabric, it would never be long enough.

“You said you know a good website for buying lace.” She looked at me significantly and raised her eyebrows, and I obediently stood up from the net wreckage and went to the computer and ordered 6 meters of black lace from cottonlace.com.

That felt like a sensible solution until the new lace arrived and I laid it down beside the mantelet.

Mr Tabubil said “Yerk.”

And my Mother-in-law said “Well that doesn’t work! What else have you got?”

I went on the google (and the ebay and the etsy) to look for a more delicate, and hopefully vintage, black lace to make a flirty ruffle with. I wanted something 3 inches wide, and then I saw the price of vintage 3 inch lace, and started looking for something 2 inches wide, or 1 inch wide – or anything I could afford, really. Eventually I came away with a bolt of sheer, filmy 1.5 inch wide vintage black lace and I was exultant. My mid 18th-century coquettery would be happening!

Looking at the mantelet in the Liotard portrait, the ruffle is barely ruffled. I stitched my lace to the mantelet’s hemmed edge, catching a small box pleat every two inches or so.

It was a very simple process, but the fabrics I was joining together were so light and delicate that it took quite a long time to complete. In bits. And fits. And then more fits. Mostly when I was sewing with other people. It was an awfully dull and fiddly sort of sewing to be doing alone.

Once it was all sewn. I added a pair of ribbon ties, and voilà! There it was. Perfectly flirty and perfectly pointless. It was CHARMING.